What is myasthenia gravis?

Last updated Dec. 17, 2025, by Lindsey Shapiro, PhD

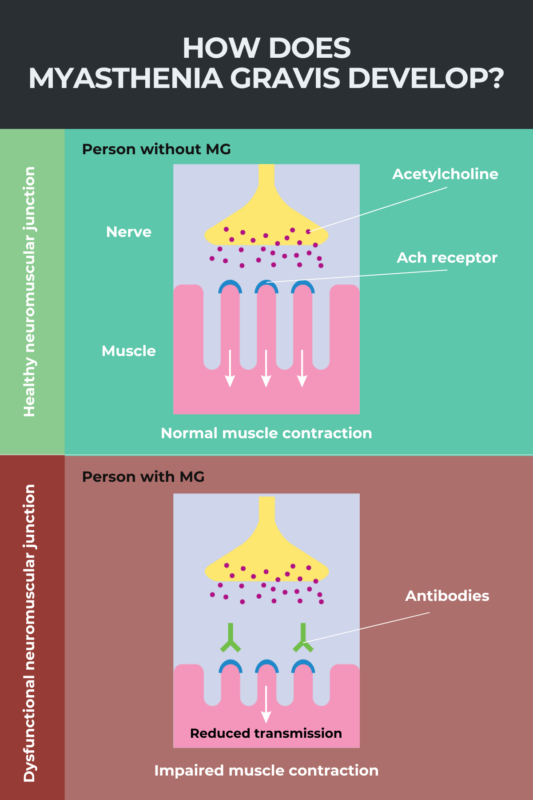

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare neuromuscular disease characterized by weakness and fatigue that can affect any muscles involved in the body’s voluntary movements. MG has an autoimmune origin, being driven by self-reactive antibodies that attack proteins involved in nerve-muscle communication.

The disease has an estimated prevalence of 14-40 cases per 100,000 individuals in the U.S., and about 150-200 cases per 1 million people worldwide. It is most common in adults, but can affect people of any age, including infants.

A person’s individual disease presentation — all of the signs and symptoms of the disorder — is influenced by the specific cause, type, and other factors. But the overall prognosis of MG is usually good, and patients typically have a lifespan that’s similar to their healthy peers. While there is no cure for MG, a number of approved and emerging treatments exist to help control its symptoms.

Causes

MG is considered to be an autoimmune disease, a condition in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. In MG, these attacks are directed against proteins necessary for the proper function of the neuromuscular junction — the site where nerve cells and muscles communicate to coordinate voluntary movements.

For most patients, MG is caused by self-reactive antibodies that target acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) — proteins that reside on muscle cells and respond to chemical signals from nerves to coordinate muscle contraction.

Less commonly, self-reactive antibodies target other proteins involved in nerve-muscle communication, such as muscle-specific kinase, or MuSK. But about 1 in 10 patients lack antibodies against any of these proteins.

The specific cause of MG autoimmune attacks is not known, but it’s believed that abnormalities in the thymus gland, a component of the immune system located in the chest, may be involved in the production or maintenance of the disease-driving antibodies.

MG is not typically considered to be an inherited disease, even though there are certain genetic factors that may increase a person’s susceptibility to develop the disease. Some people also have genetic mutations that affect nerve-muscle communication and cause congenital myasthenia, but this is considered to be a distinct clinical condition.

Types

Myasthenia gravis can be divided into multiple types. This depends on which muscles are affected, the age at which symptoms first emerge, and the exact causes contributing to the autoimmune attack.

There are three main types of MG:

- Ocular MG is marked by muscle weakness limited to eye and eyelid muscles. This type of MG generally has a good prognosis when symptoms are well controlled with treatment.

- Generalized MG, also known as gMG, is characterized by widespread muscle weakness that, as its name suggests, is not restricted to a particular muscle group. The most common type of MG, it also typically is the most severe. Many patients who go on to develop gMG will start off with purely ocular symptoms.

- Transient neonatal MG is evident in some babies born to patients with MG. It occurs when the mother’s self-reactive antibodies are transferred to the unborn baby through the placenta. While the initial symptoms can be serious, they usually disappear in the weeks or months following birth.

Individuals with MG can be additionally classified based on their age at disease onset, the type of disease-causing antibodies they have, or the presence of a thymoma, which is a tumor on the thymus gland. These specific subtypes may influence a patient’s disease presentation, prognosis, and treatment plan.

Symptoms

Muscle weakness and muscle fatigue are the hallmark symptoms of myasthenia gravis. These symptoms may come and go, and usually get worse with activity and other triggers. In most cases, symptoms reach their most severe level within a few years after disease onset.

Living with MG

Navigating Mental Health with Myasthenia Gravis

Symptom onset is most common in adulthood, but the disease can affect a person at any age. This includes children, even infants.

For most patients, the muscles of the eyes and eyelids are typically the first to be affected, regardless of whether patients continue to have an ocular form of the disease or progress to the generalized type.

Ocular symptoms may include:

- double vision, called diplopia

- eyelid droopiness, known as ptosis

- partial paralysis of eye movements.

For patients with the generalized form of the disease, muscle weakness may affect the muscles of the face, neck, throat, or limbs, or those needed for breathing.

Symptoms of generalized MG may include:

- speech problems

- difficulty chewing and swallowing

- altered facial expressions

- difficulty holding one’s head up

- trouble lifting the arms

- weak grip

- difficulty walking long distances or climbing stairs

- trouble in rising from a sitting position

- difficulty breathing.

When respiratory muscles become too weak, patients may experience a myasthenic crisis, a medical emergency that usually requires hospitalization and ventilation support. The hallmark symptoms of a mysathenic crisis are severe breathing problems.

Diagnosis

Because myasthenia gravis symptoms overlap with those from many other diseases, several tests may be needed to identify and confirm the diagnosis of MG.

The diagnostic process may involve:

- a physical and neurological examination to look for common signs of MG

- ice pack test, which is used to elicit temporary improvements in muscle strength and thereby identify the presence of MG

- a blood test to look for known MG-causing autoantibodies, such as those against AChRs or MuSK

- repetitive nerve stimulation tests to assess a nerve cell’s ability to transmit a signal to a muscle, which is diminished in MG with repetitive stimulation

- single fiber electromyography, the most sensitive diagnostic test for MG, which measures the response of individual muscle fibers to stimulation

- imaging scans, including MRI or CT scans, to look for abnormalities in the thymus gland and rule out other conditions that may cause similar symptoms to MG

- pulmonary function tests, which can be used to assess a person’s risk of respiratory failure and myasthenic crisis, or facilitate the diagnosis of patients with more severe forms of MG who experience respiratory symptoms early on in the course of the disease.

Treatment

There is no cure for myasthenia gravis, but treatments are available that can help keep symptoms under control. These may include medications, surgery, lifestyle changes, and other procedures.

In some people, MG may go into remission, allowing patients to discontinue treatment or lower the dose of certain medications. Some patients also may go into spontaneous remission in the absence of treatment.

Medications

A number of medications may be used to help control myasthenia gravis symptoms. These work via different mechanisms and generally aim to either improve nerve-muscle communication or suppress excessive immune system activity.

- Anticholinesterases, such as Mestinon (pyridostigmine bromide), are often used as a first-line treatment for MG. They work by boosting the effects of acetylcholine, the signaling molecule that instructs muscles to contract, thereby improving nerve-muscle communication and enhancing muscle strength.

- Complement inhibitors, such as Soliris (eculizumab) and Ultomiris (ravulizumab-cwvz), are used to block the activation of the immune system’s complement signaling cascade, which is thought to be implicated in MG. These treatments are approved for treating patients with gMG who are positive for anti-AChR antibodies.

- FcRn blockers, such as Vyvgart (efgartigimod afla-fcab), Vyvgart Hytrulo (efgartigimod alfa and hyaluronidase-qvfc), Rystiggo (rozanolixizumab-noli), and Imaavy (nipocalimab-aahu), are designed to enhance the clearance of the self-reactive antibodies that drive MG. Vyvgart and Vyvgart Hytrulo are both approved to treat patients with gMG who are positive for anti-AChR antibodies. Rystiggo and Imaavy are approved to treat gMG patients who are positive for anti-AChR or anti-MuSK antibodies.

- B-cell-depleting therapies, such as Uplizna (inebilizumab-cdon), work by promoting the death of B-cells, the immune cells responsible for producing antibodies, including the self-reactive ones that drive MG. Uplizna is approved for treating gMG patients who are positive for anti-AChR or anti-MuSK antibodies.

- Corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are potent anti-inflammatory medicines that broadly suppress immune activity. In MG, such medications are widely used to control symptoms.

- Nonsteroidal immunosuppressants also work to broadly suppress the immune system. Several immunosuppressants are used to control MG symptoms, all of which work via different mechanisms. Examples include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and tacrolimus.

A number of experimental treatments also are under investigation for MG.

Other interventions

In addition to standard MG medications, there are other approaches that can help ease myasthenia gravis symptoms in certain situations. These include:

- plasmapheresis, or plasma exchange, which works to filter out the component of blood that contains the self-reactive antibodies that cause MG

- intravenous immunoglobulin infusions, which provide patients with antibodies from healthy donors that serve to temporarily reset the immune system, helping to neutralize and promote the elimination of MG-driving autoantibodies

- thymectomy, a surgery to remove the thymus gland, which may reduce the amount of self-reactive antibodies, especially in patients with a thymoma, or a thymus tumor

- avoiding certain disease triggers, which may include stress, fatigue, illness, or certain medications

- other lifestyle changes, such as proper diet and exercise, to boost life quality.

Prognosis

Most people living with myasthenia gravis have a normal life expectancy, and advances in diagnosis and treatment now mean that deaths from MG are uncommon.

With proper treatment, MG symptoms can be well controlled, allowing myasthenia gravis patients to have active lives. Some patients may go into remission, where symptoms of muscle weakness are either very mild or absent, for long periods of time or permanently.

Still, MG symptoms can vary widely from patient to patient, and may be mild for some people and severe for others.

Some patients may experience a myasthenic crisis, a life-threatening emergency that arises when respiratory muscles become too weak for breathing. Nonetheless, better care and more treatment options in recent decades have significantly improved the prognosis of people with myasthenia gravis after a crisis. Most patients will survive with prompt treatment and ventilatory support in the hospital, and may still be able to go on to achieve disease control or remission.

Factors that may predict a more severe disease course or the occurrence of a myasthenic crisis include:

- older age

- having a generalized MG type, especially with respiratory muscle involvement

- having antibodies against the MuSK protein

- having a thymoma (thymus tumor).

Myasthenia Gravis News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Recent Posts

- One troubling aspect of chronic illness is when I find myself losing empathy

- Most MG patients in US start therapy without lab confirmation of disease

- Even with myasthenia gravis, ‘you still have to get up in the morning’

- New patient registry aims to collect real world evidence on MG in US

- Amgen’s Uplizna now approved in EU to treat most adults with gMG

FAQs about myasthenia gravis

The life expectancy for people with myasthenia gravis generally falls in line with normal ranges, and many patients are able to live full, active lives. Some patients also may achieve disease remission for long periods of time, or permanently.

Myasthenia gravis has an autoimmune origin and is not typically considered a heritable disease. Some people may have mutations in genes that affect the function of proteins involved in nerve-muscle communication and cause congenital myasthenia, but this is considered to be a distinct clinical condition.

Myasthenia gravis is estimated to impact about 14-40 people per 100,000 in the U.S., and about 150-200 people per million worldwide. Because it affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S., the condition is considered a rare disease.

Myasthenia gravis may be diagnosed with a range of different tests. A blood test looking for the presence of disease-causing antibodies is the main way of diagnosing myasthenia gravis. In some cases, additional nerve-muscle function tests or other evaluations may be necessary to reach a definitive diagnosis of myasthenia gravis.

There is no cure for myasthenia gravis (MG), but a number of medications and other treatments are available that can help ease its symptoms and boost patients’ quality of life. Some patients may achieve temporary or permanent disease remission with or without the help of treatments.