2 Autoantibodies Identified as Potential New Biomarkers for Myasthenia Gravis, Researchers Say

Written by |

Researchers report that two autoantibodies found in patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) may cause the disease in a subgroup of patients. These autoantibodies might also serve as biomarkers, indicating that MG is a complex disease with different causes.

The review article, titled “Agrin and LRP4 antibodies as new biomarkers of myasthenia gravis,” was published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

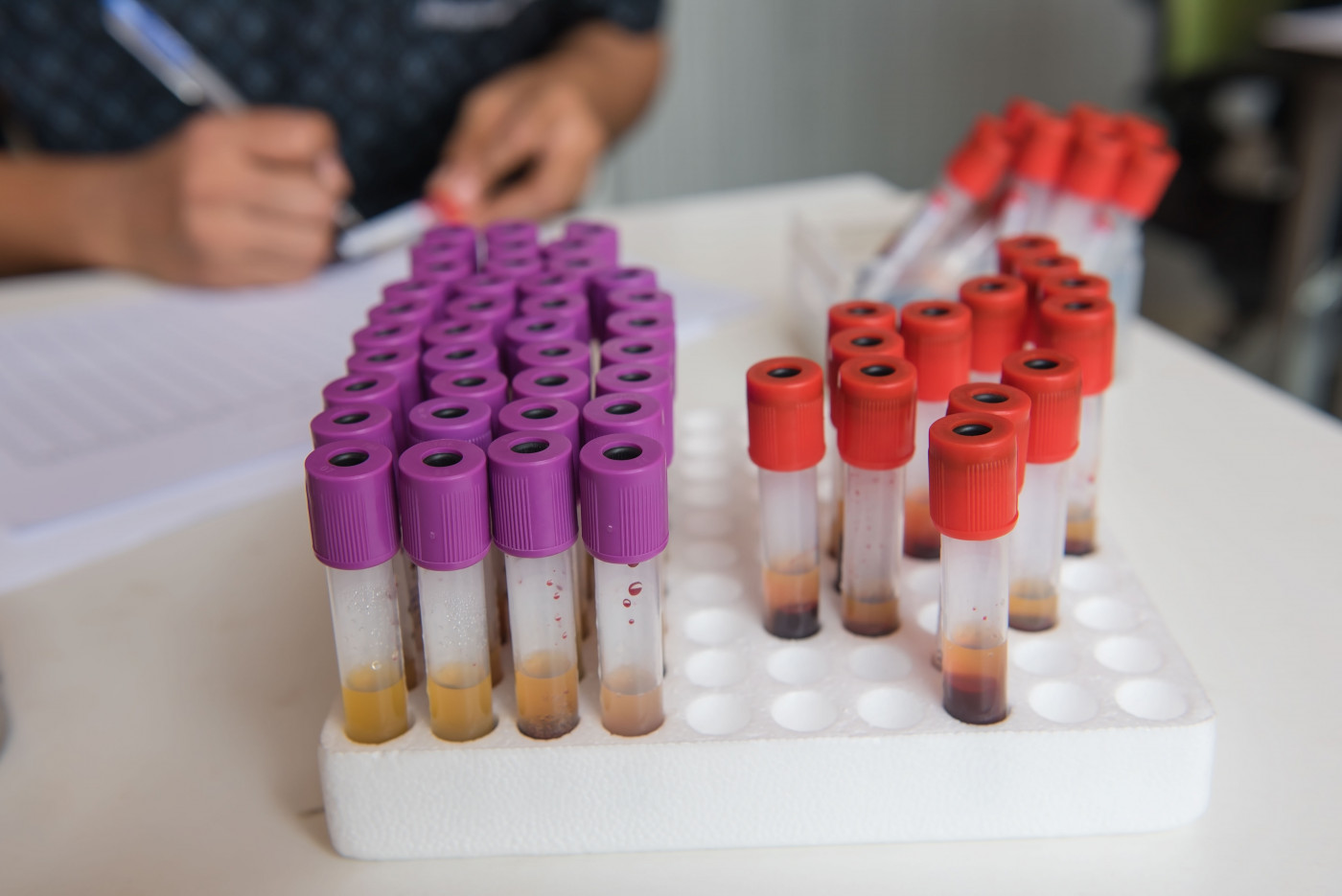

Autoantibodies are antibodies produced by a patient’s immune system that target naturally occurring substances or stuctures in the body. In this case, two proteins that form a part of neuromuscular junctions are the targets. Neuromuscular junctions, a kind of synapse, are the points at which nerve cells send signals to muscle cells.

In myasthenia gravis patients, defects in neuromuscular junctions are the cause for the characteristic fatigue and weakness of voluntary eye, limb, and bulbar muscles in the neck and jaw, which control speech, chewing, and swallowing.

The recently discovered autoantibodies target the proteins agrin and low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 4 (LRP4), both of which are required for the proper formation of neuromuscular junctions. Mice lacking either of these two proteins do not form neuromuscular junctions at all.

Autoantibodies that target acetylcholine receptors (AChR), proteins that are essential to proper signaling at neuromuscular junctions, are present in roughly 80% of patients with MG.

And autoantibodies that target the enzyme called muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK), also found at neuromuscular junctions, are present in 40% of myasthenia gravis patients who are negative for AChR autoantibodies. The autoantibodies against agrin and LRP4 cause a disease that mimics MG in animals, suggesting they also cause the disease in humans.

In 10% of patients, neither AChR nor MuSk autoantibodies can be found. They have a form of the disease called double-seronegative MG. Agrin and/or LRP4 autoantibodies are present in these patients, which may explain how the disease occurs in this subgroup. This may also mean that these autoantibodies might be used as biomarkers of the disease.

The authors of the review point out that it is too early to confirm observations that anti-LPR4 and/or anti-agrin antibodies are present in more females than males. Also, studies with larger groups of patients must be done before it can be confirmed that these patients tend to have generalized disease, without developing thymoma. Thymoma is a tumor in the thymic gland and is usually benign. It can be associated with myasthenia gravis.

“It is foreseeable that MG could be subgrouped into different categories based on a combination of antibodies, each with unique symptoms,” the authors concluded.

“Future systematic studies of large cohorts of well-diagnosed MG patients are needed to determine whether each group of patients would respond to different therapeutic strategies. Results should contribute to the goal of precision medicine for MG patients,” they added.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.