Intensive treatment most needed early in MG course: Study

Younger patients, women seen facing higher death risk

Written by |

Many adults with myasthenia gravis (MG) need intensive treatment in the first year after diagnosis, with younger patients and women facing a higher risk of death as the disease progresses, a study found. The researchers said the results point to a need for better treatment options.

The study, “Tracking myasthenia gravis severity over time: Insights from the French health insurance claims database,” was published in the European Journal of Neurology.

MG is caused by self-reactive antibodies that mistakenly target proteins involved in nerve-muscle communication, leading to muscle weakness and fatigue. While advances in treatment have improved outcomes, it’s important to understand how MG progresses in real-world settings.

Symptoms usually stabilize after an initial period of acute disease. However, many patients continue to experience exacerbations, or sudden episodes of muscle weakness and fatigue, often triggered by physical activity.

Sometimes exacerbations occur despite treatment, requiring rescue with plasmapheresis, also known as plasma exchange, or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). In severe cases, patients may need to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and be placed on a ventilator for breathing support.

Understanding disease progression

To better understand how MG progresses over time, researchers in France looked into how severe the disease became over the course of up to eight years using data from the French National Health Insurance Database, which covers nearly the entire French population.

The study identified 14,459 patients, with a mean age of 62.3, who had filed insurance claims related to MG between 2013 and 2020. The sample included 6,354 newly diagnosed patients. Most patients were on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, often the first-line treatment for MG, and/or corticosteroids. The use of nonsteroidal immunosuppressants was reported in fewer than half of the patients (45%).

“Further research into treatment sequences in individual patients and the relationship between treatment changes and disease manifestations would be important to perform in order to understand why potentially life-threatening MG crises occur episodically over time,” the researchers wrote.

More than two-thirds (69.6%) of newly diagnosed patients were men, a percentage that was higher than that found when considering all patients in the study (46.1%). In 2020, there were an estimated 234 cases per million adults in France, with the disease being slightly more common in women than in men (246 cases per million vs. 221 cases per million).

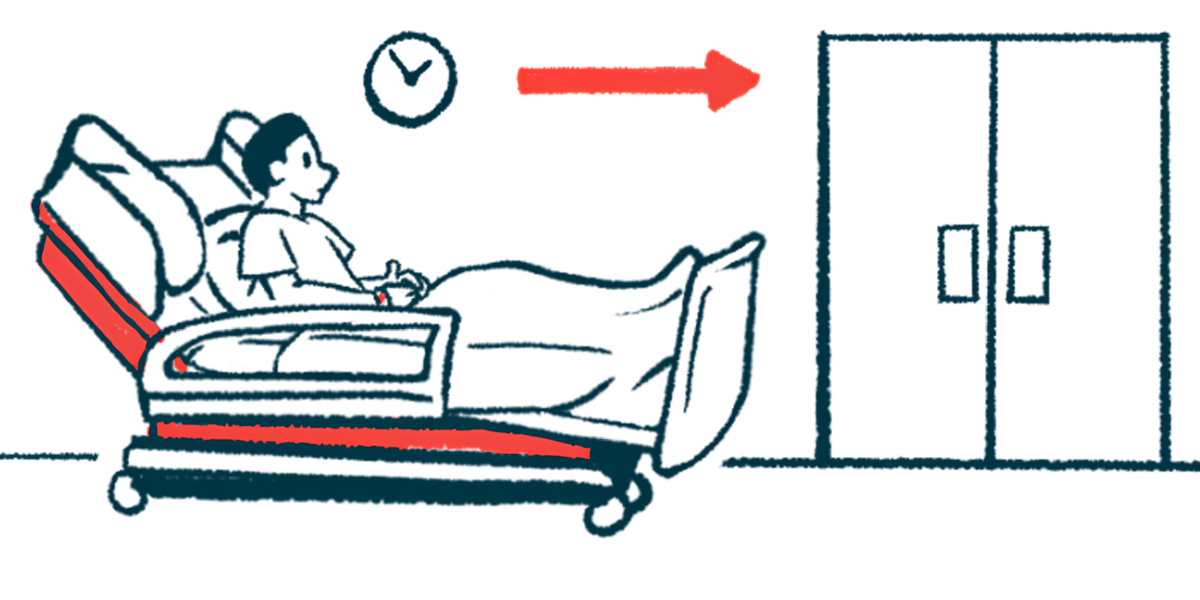

About one-third (34.6%) of newly diagnosed patients were admitted to the ICU at least once, mostly in the first year after filing their first MG-related claim (index date), which was used as a proxy for the date of diagnosis (23.3%). Admissions to the ICU became less frequent over time, with 3% of patients requiring this type of care in the seventh year after being diagnosed.

Patients also stayed longer in the intensive care unit (ICU) in the first year of diagnosis (s mean of 3.8 days) than in the second or seventh year (mean of 1.03 days and 0.41 days, respectively). The use of plasmapheresis or IVIG also decreased over time, suggesting that this type of rescue treatment is most often needed early in the course of the disease.

“Nonetheless, around 8% of patients were admitted to an ICU each year for the remainder of the follow-up period, and around 5% received IVIg each year,” the researchers wrote.

These data on the use of rescue treatment are “indicative of poor disease control” and “make a strong case for the implementation of innovative therapies and broader access early on in the disease course,” the researchers wrote.

Over the follow-up period, 2,430 (16.8%) patients in the study died, with annual death rates of 4.15% for men and 2.62% for women. At seven years of follow-up, women were more likely to have survived than men (84% vs. 77%).

Similar observations were made in the group of patients who were newly diagnosed. In those patients, the median time to death after the index date was 2.47 years. Their risk of death was 8% higher compared with the general population in France, and was especially higher among women (15% higher) and patients younger than 65 (50% higher).

“Life expectancy in these patients was close to that of the French general population, although some subgroups of patients continued to be hospitalized in ICUs and required rescue therapies across the duration of the follow-up,” the researchers wrote.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.