Study Explains Why MuSK MG Patients Relapse After Rituxan Therapy

Written by |

A recent study by researchers from Yale University furthers understanding about why certain myasthenia gravis (MG) patients who were treated with Rituxan (rituximab) may relapse.

Findings of the study, “Autoantibody-producing plasmablasts after B cell depletion identified in muscle-specific kinase myasthenia gravis,” were published at The Journal of Clinical Investigation-Insight.

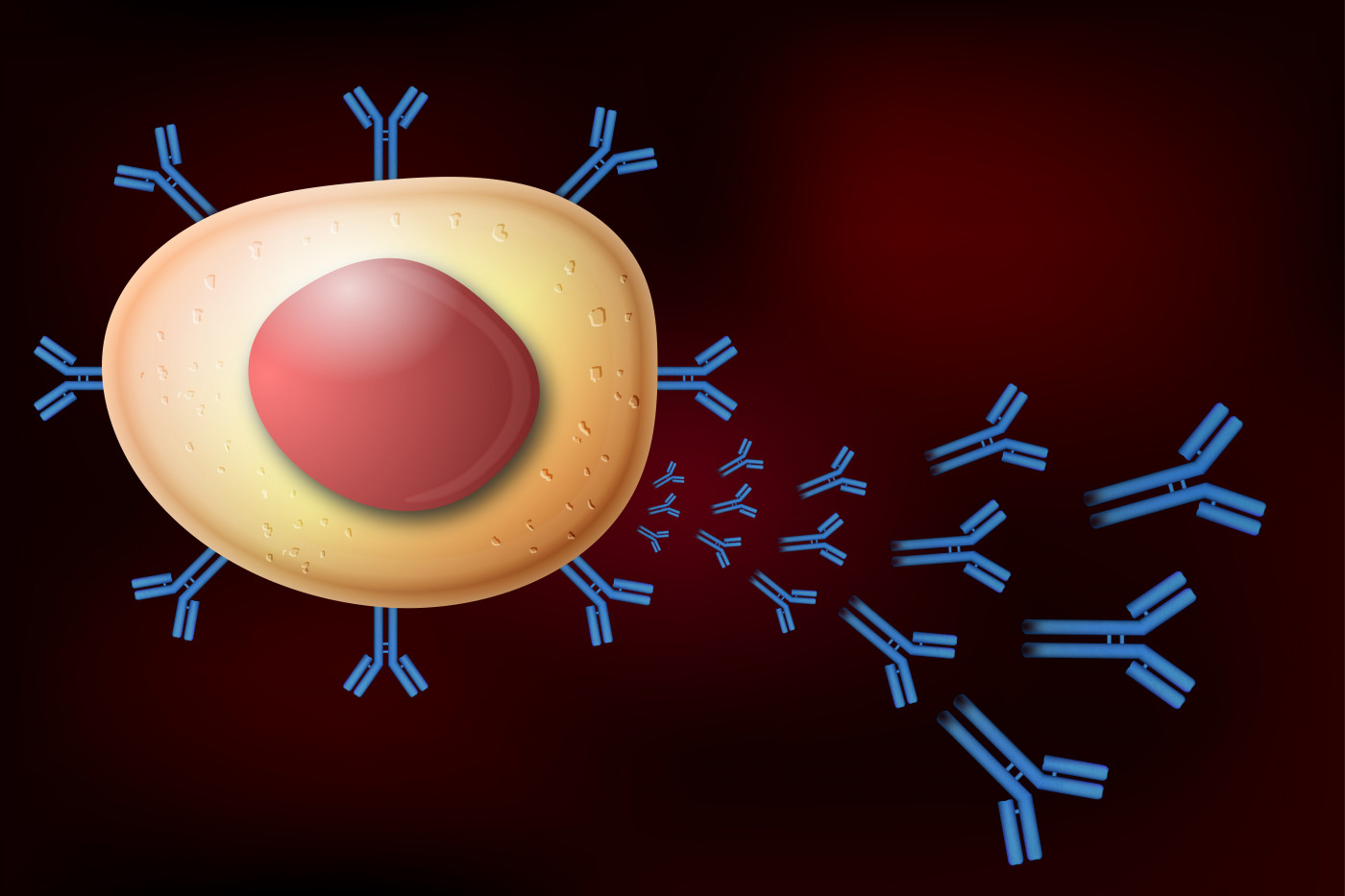

MG is an autoimmune disorder that is caused by the production of antibodies that attack the communication points between motor nerve cells and muscle tissue, leading to weakness and fatigue. This study found that a specific subset of immune B cells called plasmablasts were found to be responsible for relapsed production of muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) autoantibodies in MA patients upon treatment with Rituxan.

These autoantibodies are produced by immune B cells that are not functioning normally. Commonly, the autoantibodies found in MG patients recognize the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) in the muscles, preventing them from contracting. However, they also can recognize other proteins such as MuSK.

The use of therapies that can induce a depletion of B cells has been shown to be beneficial to MG patients, because they can reduce the levels of autoantibodies in circulation and sustain clinical improvements. However, the majority of the MuSK MG patients seem unable to present a long-term positive response to such therapeutic strategy, relapsing even upon achieving B cell depletion-induced remission.

A research team at the Yale School of Medicine wanted to shed light into this matter and understand what happened upon B cell depletion therapy that could enable MG relapse in patients positive for MuSK autoantibodies.

To achieve this the researchers tried to identify which cells were responsible for the production of autoantibodies in three cases of patients with MuSK MG who relapsed after Rituxan therapy, an immunotherapy used to induce therapeutic B cell depletion.

They found that upon Rituxan treatment, a subset of B cells called plasmablasts produced new autoantibodies attacking the MuSK protein. Although the treatment targeted all abnormal B cells that initially caused the disease, it probably failed to completely deplete the immune memory cells subset – responsible for repopulation of the immune B cells repertoire. The memory cells that were able to evade the treatment were producing abnormal plasmablasts, which, in turn, were activated to produce autoantibodies, leading to MuSK MG relapse.

“While therapy with rituximab [Rituxan] eliminates B cells, they remain abnormal after regenerating and contribute to relapse,” Kevin C. O’Connor, PhD, associate professor of neurology and co-senior author of the study, said in a press release.

Based on these findings, evaluation of the remaining B cells upon therapy could have potential prognostic value for identification of patients at risk for disease relapse. Further studies are necessary to further explore this strategy as a biomarker for guided re-treatment decisions.

“Disease relapse following successful rituximab [Rituxan] treatment could be predicted, allowing physicians to tailor therapy on an individual basis,” said Richard Nowak, MD, co-senior author of the study and director of the Yale Myasthenia Gravis Clinic.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.