Rituxan Lessens Disease Severity in Myasthenia Gravis Irrespective of Type of Autoantibodies, Study Reports

Written by |

Treatment with Rituxan (rituximab) benefits patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) with either anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) or muscle-specific tyrosine kinases (MuSKs) antibodies, a study has found.

Patients with MuSKs antibodies, however, may experience greater improvement, including less time to achieve remission, fewer exacerbations, and need for hospitalizations following treatment.

The study, “Differential response to rituximab in anti-AChR and anti-MuSK positive myasthenia gravis patients: a single-center retrospective study” was published in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences.

MG is an autoimmune disease caused by the abnormal production of autoantibodies against AChRs in 80% of the cases. Less frequently, the disease can be caused by a different type of autoantibody against MuSKs, known to affect up to 40% of patients. In both cases, patients experience muscle weakness, a lack of muscle endurance, and extreme fatigue.

Conventional therapy for the management of MG includes the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, immunosuppressive therapies, such as azathioprine or cyclosporine, or thymectomy (surgical removal of the thymus, which is key for the production of antibodies).

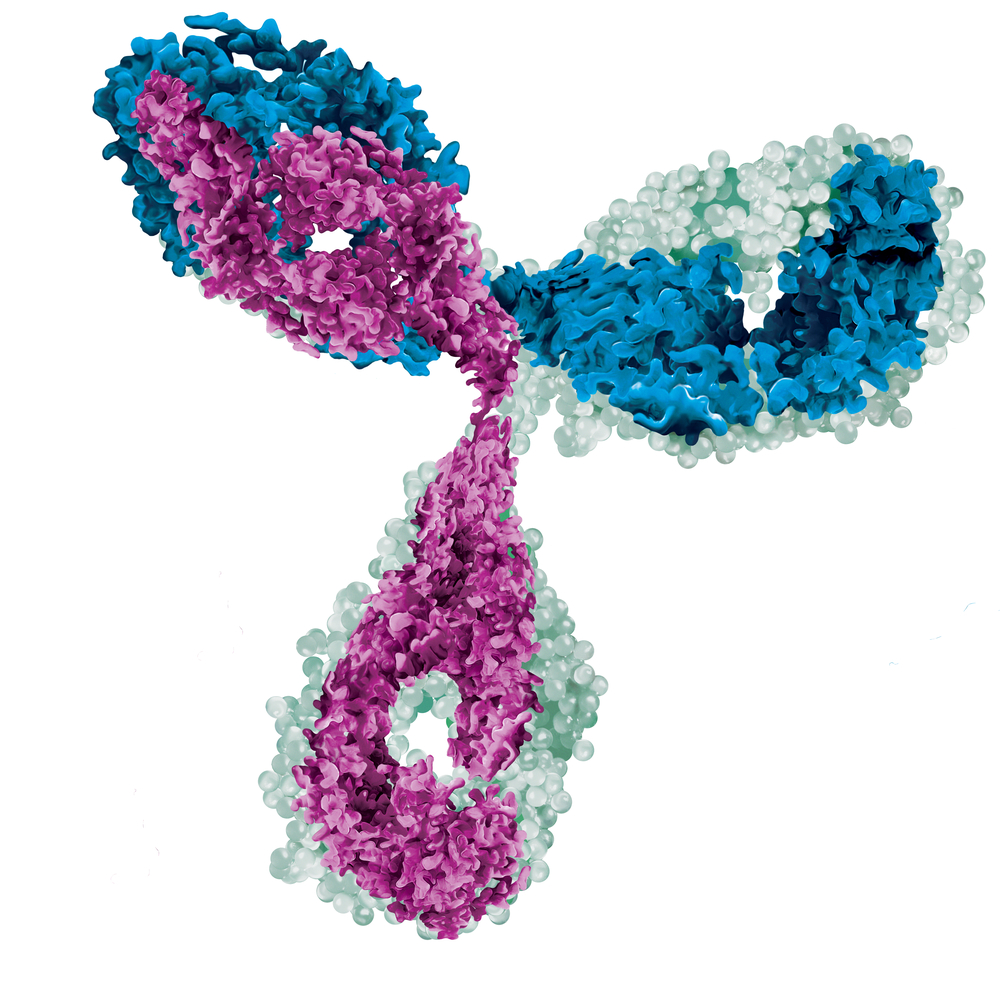

Rituximab, sold under the brand name Rituxan in the U.S. and MabThera in Europe, among others, is an antibody that leads to rapid depletion of B-cells (immune cells that produce antibodies) and has shown promise as a therapy for MG.

However, few studies have addressed whether patients with AChRs or MuSKs autoantibodies respond differently to rituxan.

A group of researchers at the Yale School of Medicine performed a retrospective analysis of the long-term responses of 33 MG patients (24 women and nine men, average age 35.9 years), with AChRs (17 patients) and MuSKs (16 patients) antibodies, followed at the Yale Myasthenia Gravis Clinic. The average follow-up was five years.

Patients were eligible for rituximab if the immunotherapy dose could not be lowered due to clinical relapse, symptoms were not controlled by immunotherapy, or current therapy caused severe adverse side effects.

Because there is no established protocol for rituxan for MG patients, the therapy was given at the same dose used for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (blood cancer) patients: four weekly infusions at a dose of 375 mg/m2. Patients were given two or four cycles of rituxan, with one cycle defined as one infusion per week for four consecutive weeks. The interval between cycles was six months.

On average, patients received 3.1 cycles of rituxan. The majority of patients (29 of 33) received treatment with the corticosteroid prednisone before starting rituxan. More patients with MuSK antibodies (11 of 16) were given other therapies prior to rituxan than those with AChRs (four of 17). On the contrary, fewer MuSK patients underwent thymectomy (five of 16) compared to AChRs patients (15 of 17).

At the start of the analysis, the entire group had a median score of 2 in the clinical severity scoring system from the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) classification system. The scale ranges from normal (zero) up to severe disease (score five).

Twelve months after rituxan treatment, all patients improved and became asymptomatic, achieving a score of zero. This score was maintained until last follow-up.

A total of 21 patients, 12 with AChRs and nine MuSK, achieved clinical remission. MuSK patients achieved remission sooner at 230 days (average), while AChRs patients took 441.4 days (average).

“Remission was defined as when the patient achieved “asymptomatic” status based on the MGFA classification and had not relapsed for 12 months,” researchers wrote.

Sixteen patients relapsed after treatment with rituxan. The relapse rate was higher for AChRs patients (58.8%, 10 patients) compared to MuSK (37.5%, six patients). No differences were seen in the time to relapse.

Among patients who received three or more cycles of rituxan, those with MuSK relapsed significantly later than AChRs patients. These patients also had more hospitalizations due to MG symptoms than those with MuSK.

Additionally, researchers observed that rituxan reduced the mean dose of prednisone in both groups: In AChRs patients, prednisone was reduced from a mean of 46.8 mg/day (start of the study) to 17.9 mg/day at the last follow-up; in MuSK patients, prednisone decreased from a mean 30.9 mg/day to 2.8 mg/day.

Overall, these findings suggest that “rituximab therapy is a reasonable option for both AChR+ [positive] and MuSK+ [positive] generalized MG patients, especially those with difficult to control disease,” researchers wrote.

“While there was no significant difference between these groups in terms of clinical improvement, symptom-free state, and prednisone burden, MuSK+ MG patients may experience greater benefits, including earlier time to remission, fewer exacerbations and hospitalizations post-treatment,” they concluded.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.