Levels of Certain B- and T-cells Linked to Ocular MG Turning Generalized

Low blood levels of regulatory immune cells that prevent autoimmune responses, and high levels of antibody-producing memory B-cells may cause ocular myasthenia gravis (MG) to progress to generalized MG, an early study suggests.

The study, “Comparison of peripheral blood B cell subset ratios and B cell-related cytokine levels between ocular and generalized myasthenia gravis,” was published in the journal International Immunopharmacology.

MG, an autoimmune disorder, occurs when a person’s immune system produces antibodies that mistakenly attack and disrupt the function of proteins at the neuromuscular junction — the site at which nerve cells and muscles communicate with each other. This interrupts the transmission of nerve impulses to muscles, leading to muscular weakness, a hallmark of MG.

There are several forms of MG, depending on the time of disease onset, the cause of the neuromuscular problems, and the muscle groups affected.

Ocular MG is marked by weakness in the muscles controlling eye and eyelid movement, while people with generalized MG have more severe and widespread disease, affecting muscles that include those of the face, arms, and legs.

Researchers estimate that 50-60% of patients with ocular MG progress to generalized MG within two years of disease onset. However, the mechanisms that determine onset and progression remain unclear.

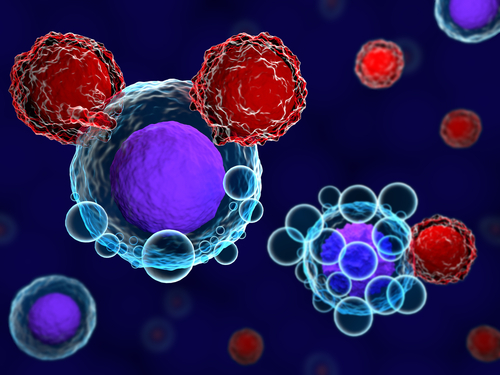

Central to the autoreactive immune responses occurring in MG are subsets of immune T-cells and B-cells.

T helper (Th) cells play a central role in directing the immune response against proteins at the neuromuscular junction. In addition, specific subsets of B-cells, particularly memory B-cells, drive the production of self-reacting antibodies that target proteins at the neuromuscular junction, impairing its normal function.

Memory B-cells are long-lived cells, crucial to the immune system “remembering” microbes or foreign particles that the body was previously exposed to. In cases of reinfection, these cells quickly raise a highly specific response to fight the threat.

In contrast, regulatory T-cells (Tregs) and regulatory B-cells (Bregs) keep the body’s immune response in check by regulating or suppressing other immune cells. They can control, or regulate, the immune response to the body (self) and to foreign particles, which is important to help prevent autoimmune reactions.

In fact, lower than normal levels of Tregs and Bregs have been found in patients with MG. These levels relate not only with disease development, but also with its severity.

Immune cells may also contribute to autoimmune conditions by releasing chemical messengers known as cytokines, which are used by these cells to communicate.

However, it remains unclear how each of these players is activated during MG, and how they may contribute to ocular MG progressing to generalized disease.

To address these questions, researchers in China measured the levels of these immune cells in patients with both forms of the disease.

They analyzed the blood of 16 people with ocular MG, 31 with generalized MG, and 20 healthy individuals serving as controls. Then they compared the differences in T- and B-cell subsets and related cytokines among these three groups.

Tests suggested that a reduction in the levels of Tregs and Bregs, and an increase in the levels of memory B-cells, might correlate with the progression of ocular to generalized MG.

Tregs and Bregs were relatively more abundant in patients with ocular disease — a mean of 6.99% and 6.83%, respectively — compared to those with generalized MG — 4.18% and 4.10%, respectively.

Conversely, patients with generalized MG had a greater proportion of memory B-cells (34.67%) than did those with ocular MG (23.13%). In people with either disease, however, memory B-cell levels were higher than in healthy people (15.16%).

Cytokines such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-17 also seemed to play an important role. Serum IL-10 levels were significantly higher in patients with ocular disease, compared to those with generalized MG or to controls.

IL-2 levels were higher in both MG patient groups compared to controls, while IL-6 and IL-17 were present in greater concentrations among people with generalized MG.

“[W]e found that reduced proportions of Tregs and Bregs … and increased proportions of memory B cells … may be important in the progression of oMG [ocular MG] to gMG [generalized MG]. Moreover, cytokines such as IL-17 and IL-10 may play important roles in the development of gMG,” the researchers wrote.

“The imbalance of T and B cell-mediated immune response mechanisms may trigger oMG production and further induce oMG progression to gMG,” they added.